Arc

Core77 Design Awards 2024 Student Runner Up, Interaction

Arc is a new kind of overhead projector that enables kids to co-create stories and worlds— and be immersed in them together. Designed with those with language barriers in mind, the device aims to help all kids feel a greater sense of belonging by lowering barriers for co-creating and engaging a shared sense of wonder.

Duration

14 Weeks, Fall 2023Course

“Materialized Agenda”— Senior Products StudioProblem Framing

User Testing and Research

Physical Prototyping

SolidWorks, Rhino

Keyshot

How it Works

A circular form affords everyone around the object equal agency to create an image together, with the outer perimeter being understood as "ground" and the middle of the circle "sky."

Instead of a flat lens that projects an image onto the wall (like a regular analog overhead projector), this one uses a spherical lens to map the circular image all around the ceiling and upper walls of the room.

The result is a projected environment directly immersing users in the world they are creating together at their fingertips, in real time.

Colored tiles and markers lower the barrier for storytelling, enabling collaboration and communication that goes beyond language.

Intended to be facilitated by a teacher or similar figure, there are options to change the color and brightness of the light, expanding storytelling capabilities. The “stage” can also rotate at an adjustable speed, affectively animating the created image to spin overhead.

Inspired by the magic of analog light projections and the way they bring the people in a room together.

This interaction is about fostering a sense of belonging that transcends words, cultures, and backgrounds.

This interaction is about fostering a sense of belonging that transcends words, cultures, and backgrounds.

Phase 1— Developing an Agenda

The objective of the project was to materialize an agenda that is personally important to me as a designer. Through considering what kind of world and interactions I want to help realize, I decided to design for intimacy and connection; interactions that foster belonging through feelings of being seen and heard.

Why Children with Language Barriers

A fairly abstract agenda required me to narrow down a target user group, prompting the question, what groups may be more prone to feelings of loneliness?

One part of my life here (teaching Sunday School to children with varying comfort levels in English) Pittsburgh’s large refugee population, and my own as well as others around me’s experiences as immigrants led me to target immigrant and refugee children whose language barriers may make it harder to feel a sense of belonging.

A fairly abstract agenda required me to narrow down a target user group, prompting the question, what groups may be more prone to feelings of loneliness?

One part of my life here (teaching Sunday School to children with varying comfort levels in English) Pittsburgh’s large refugee population, and my own as well as others around me’s experiences as immigrants led me to target immigrant and refugee children whose language barriers may make it harder to feel a sense of belonging.

Why Does This Matter?

Global Migration is Higher Than Ever

“More than 230 million people, 20% of them young children, live in countries in which they were not born.”

“More than 230 million people, 20% of them young children, live in countries in which they were not born.”

Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, “Phenomenology of Inclusion, Belonging, and Language”

Immigrant Children Face Higher Risk of Bullying

“... Not only that, they often deal with frequent micro-aggressions related to their choice of food, clothing, religion, manners, and other customs.”

“... Not only that, they often deal with frequent micro-aggressions related to their choice of food, clothing, religion, manners, and other customs.”

Shenfield, “Understanding The Challenges Faced By Immigrant Children”

This Affects Long-Term Sense of Self-Esteem and Worth

“Students' loss of self-esteem and self-worth ... are directly related to the persistence of their experiences of loneliness.”

“Students' loss of self-esteem and self-worth ... are directly related to the persistence of their experiences of loneliness.”

Kirova, “Social Isolation, Loneliness and Immigrant Students' Search for Belongingness”

The Opportunity: The Power of Objects and Play to be Platforms for Inclusivity

“The ‘cure’ for helplessness was seen from the point of view of pedagogy of loneliness as a means of creating a school environment in which all children belong. Pedagogical thoughtfulness and tactfulness on the part of the teacher are required so that immigrant students can be provided with more ... opportunities to connect to their peers as they participate in shared meaningful experiences as a possibility to form social bonds.”

Kirova, “Social Isolation, Loneliness and Immigrant Students' Search for Belongingness”

Research— Visit to a Local Refugee Kids’ Weekend Program

Pittsburgh is home to a large refugee population, with people from countries everywhere including Bhutan, Somalia, Iraq, Iran, Liberia, Sudan, and more.

I contacted and visited a local kids’ weekend program that serves many of these families’ children as a positive and joyful community to help these children thrive in their new lives here. The goal was to observe the context that the object might live in.

I contacted and visited a local kids’ weekend program that serves many of these families’ children as a positive and joyful community to help these children thrive in their new lives here. The goal was to observe the context that the object might live in.

Phase 2— Concept Generation

Field Research and Brainstorming

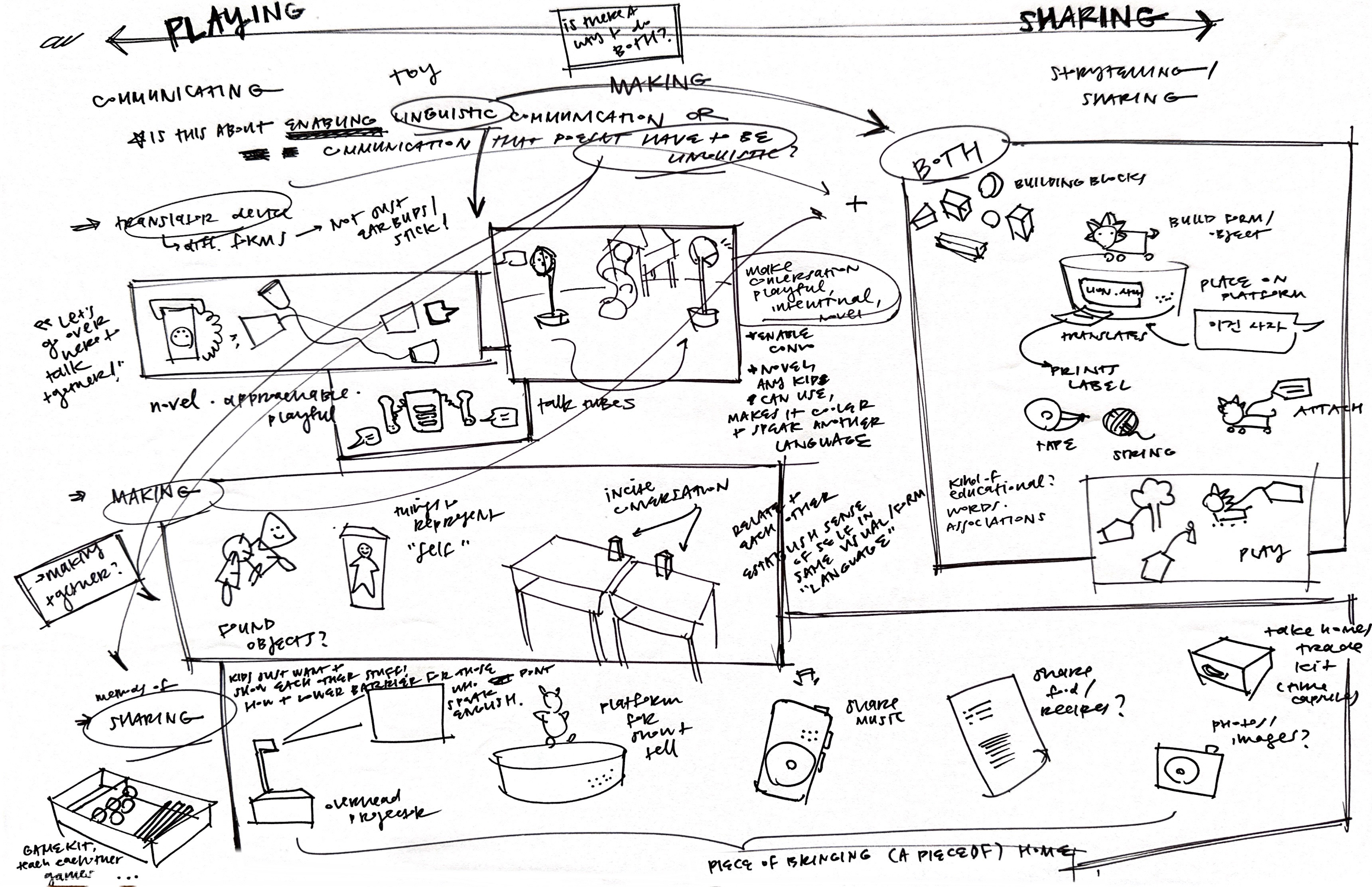

I started by going broad: what helps kids play together? What helps them connect, and how can I help bridge the most prominent gaps?

I collected relevant examples that helped me think about how my object might incorporate language, music, making, games, food, and personal items.

Some questions I asked during this phase:

“Is this about enabling linguistic communication, or communication that doesn’t have to be linguistic?”

“Is this about affording play (meaning it could be as “subtle” as furniture/infrastructure), or sharing (more “defined” interaction through a storytelling game or translating device)? Is there a way to do both?”

I started by going broad: what helps kids play together? What helps them connect, and how can I help bridge the most prominent gaps?

I collected relevant examples that helped me think about how my object might incorporate language, music, making, games, food, and personal items.

Some questions I asked during this phase:

“Is this about enabling linguistic communication, or communication that doesn’t have to be linguistic?”

“Is this about affording play (meaning it could be as “subtle” as furniture/infrastructure), or sharing (more “defined” interaction through a storytelling game or translating device)? Is there a way to do both?”

Research— Interviews

I sought perspectives from relevant voices (immigrants, immigrant parents, teachers, and more.) Here were a few key insights:

Co-Creating is Key

“I got close to people through drawing... I was always drawing in class. I became friends with someone because he started drawing back to me one day.”

“I got close to people through drawing... I was always drawing in class. I became friends with someone because he started drawing back to me one day.”

Yoosung, Immigrant

The More Intuitive, the Better

“I appreciated games like handball that were straightforward to understand, almost analog? Like the difference between trying to learn bop-it versus just playing with a teddy bear together.”

“I appreciated games like handball that were straightforward to understand, almost analog? Like the difference between trying to learn bop-it versus just playing with a teddy bear together.”

Sharon, Immigrant

“No One Has to Teach Kids How to Play”

“... All kids do it instinctively. Kids become friends through built connections over time that happen primarily through play.”

“... All kids do it instinctively. Kids become friends through built connections over time that happen primarily through play.”

Irene, Child Psych Major and Teacher

Criteria Development

These helped me narrow down the kind of object and interaction I wanted to design. I developed three important criteria for my designed interaction:

These helped me narrow down the kind of object and interaction I wanted to design. I developed three important criteria for my designed interaction:

Used By Everyone

Used By EveryoneOne of my leading concepts had been some sort of translation device. However, something that only the “new kid” uses may be alienating. The object needed to be something that everyone wanted to engage with.

Lowers Barriers for Storytelling

Lowers Barriers for StorytellingShapes, colors, mark-making tools would help expand story-telling capabilities beyond just language.

Immersive and Enchanting

Immersive and EnchantingSeeing this image was pivotal in the concept development. It reminded me of the magic and intimacy of using overhead projectors in grade school, something I definitely wanted to bring into this interaction.

Narrowed Concept Generation

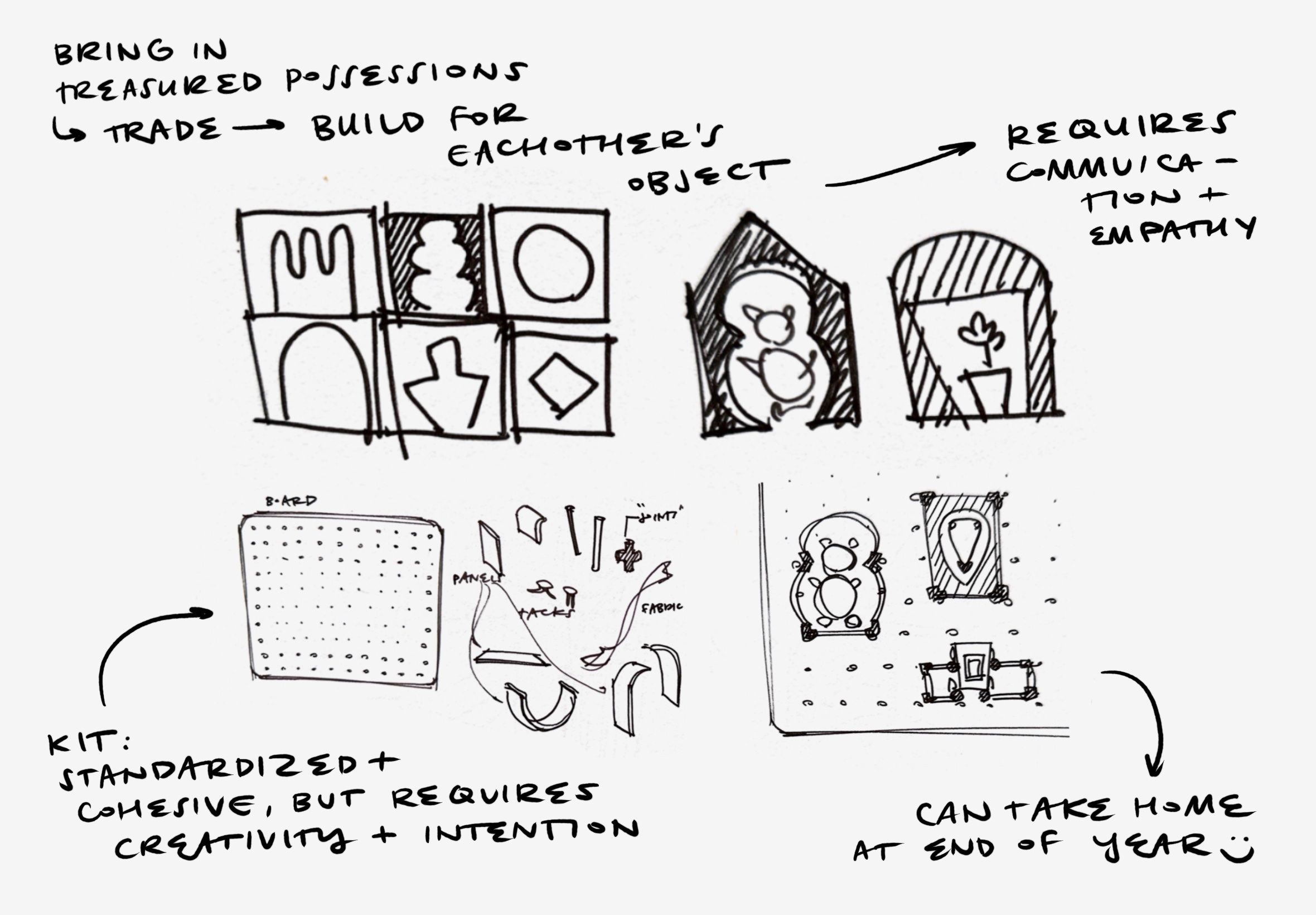

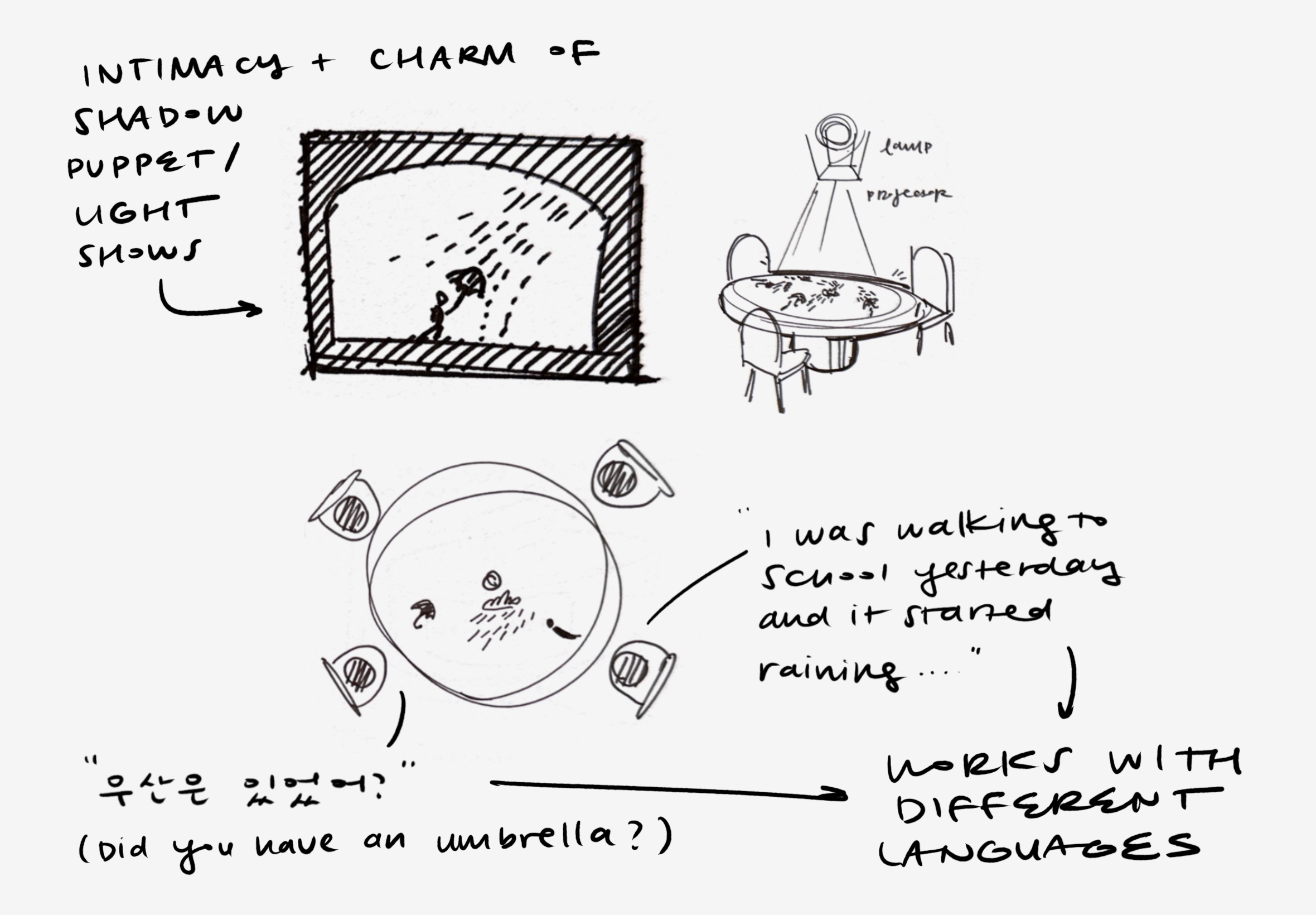

From here, I developed three, more refined concepts based on the narrowed criteria:

From here, I developed three, more refined concepts based on the narrowed criteria:

Modular kit for kids to build personalized displays for each others’ treasured objects

![]()

Lamp/table that projects animations generated in real time of kids’ stories as they share

![]()

Object building kit and translation platform

![]()

Final Concept Development

I chose to move forward with the projection lamp idea, but there were many questions to resolve. My next step was to brainstorm more refined concepts around an object that enabled and enhanced storytelling through light projection. Things that came to mind included exquisite corpses, Mad Libs, View-Master toys, and projector night lights.

I chose to move forward with the projection lamp idea, but there were many questions to resolve. My next step was to brainstorm more refined concepts around an object that enabled and enhanced storytelling through light projection. Things that came to mind included exquisite corpses, Mad Libs, View-Master toys, and projector night lights.

This evolved to an idea for a circular shadow puppet theatre that projects around the room:

Concerns about the light projecting directly into the childrens’ eye level led to the final concept for a new kind of overhead projector.

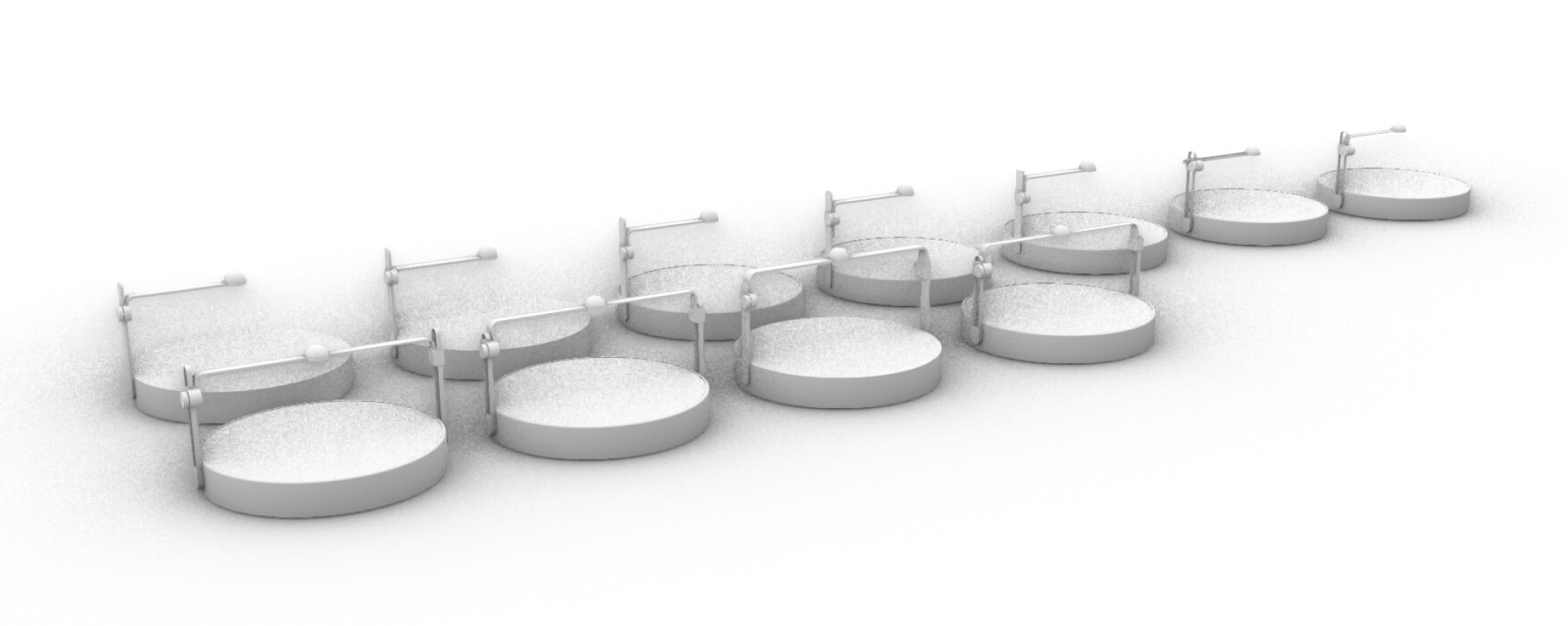

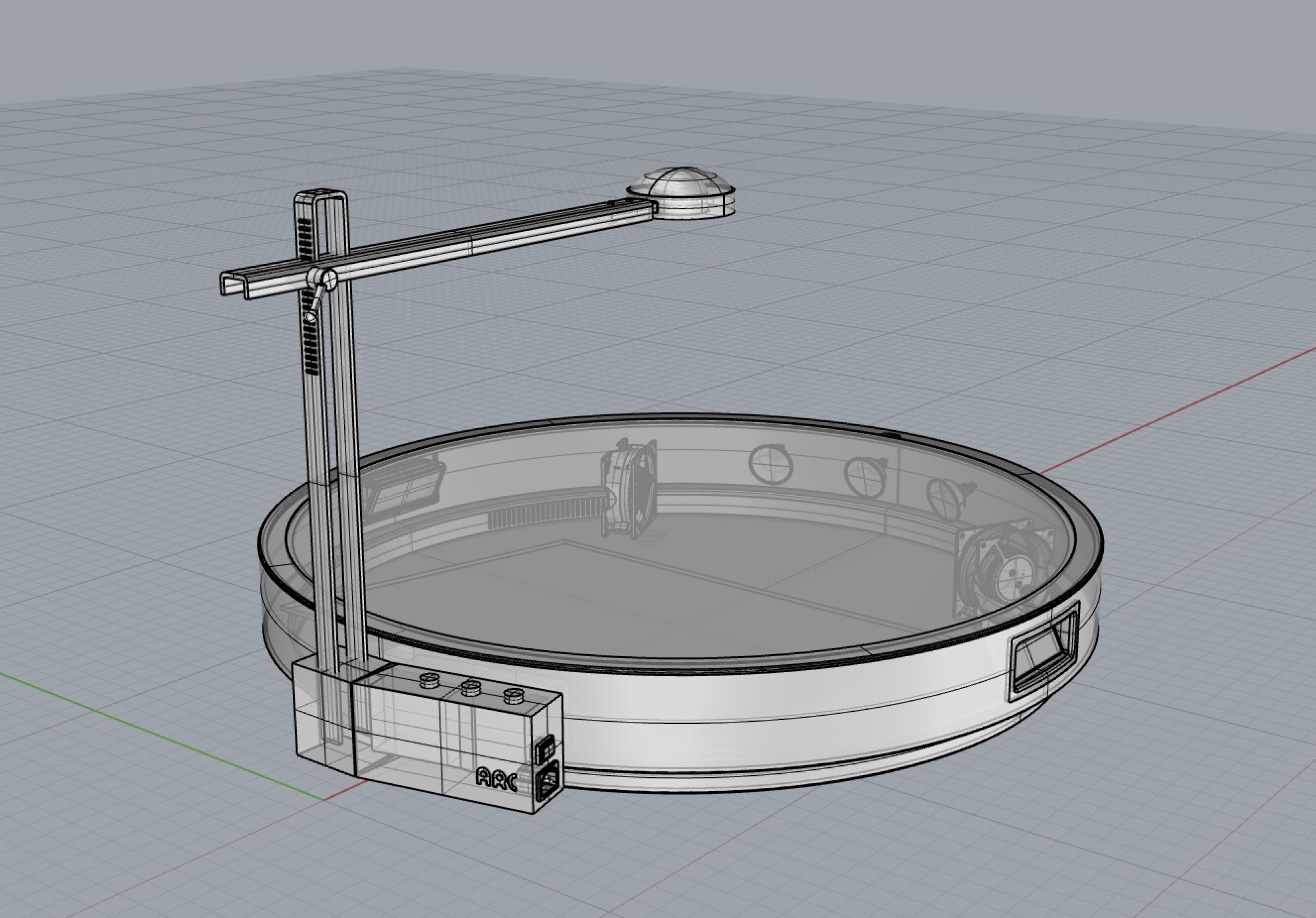

I considered a few overall form factors— a transportable, flat-surface device, a table, and a dome— before landing on the transportable device. It would be more versatile, and could be used either on another table surface or on the floor.

I considered a few overall form factors— a transportable, flat-surface device, a table, and a dome— before landing on the transportable device. It would be more versatile, and could be used either on another table surface or on the floor.

Phase 3— Form, Execution, and Testing

Follow-Up Research

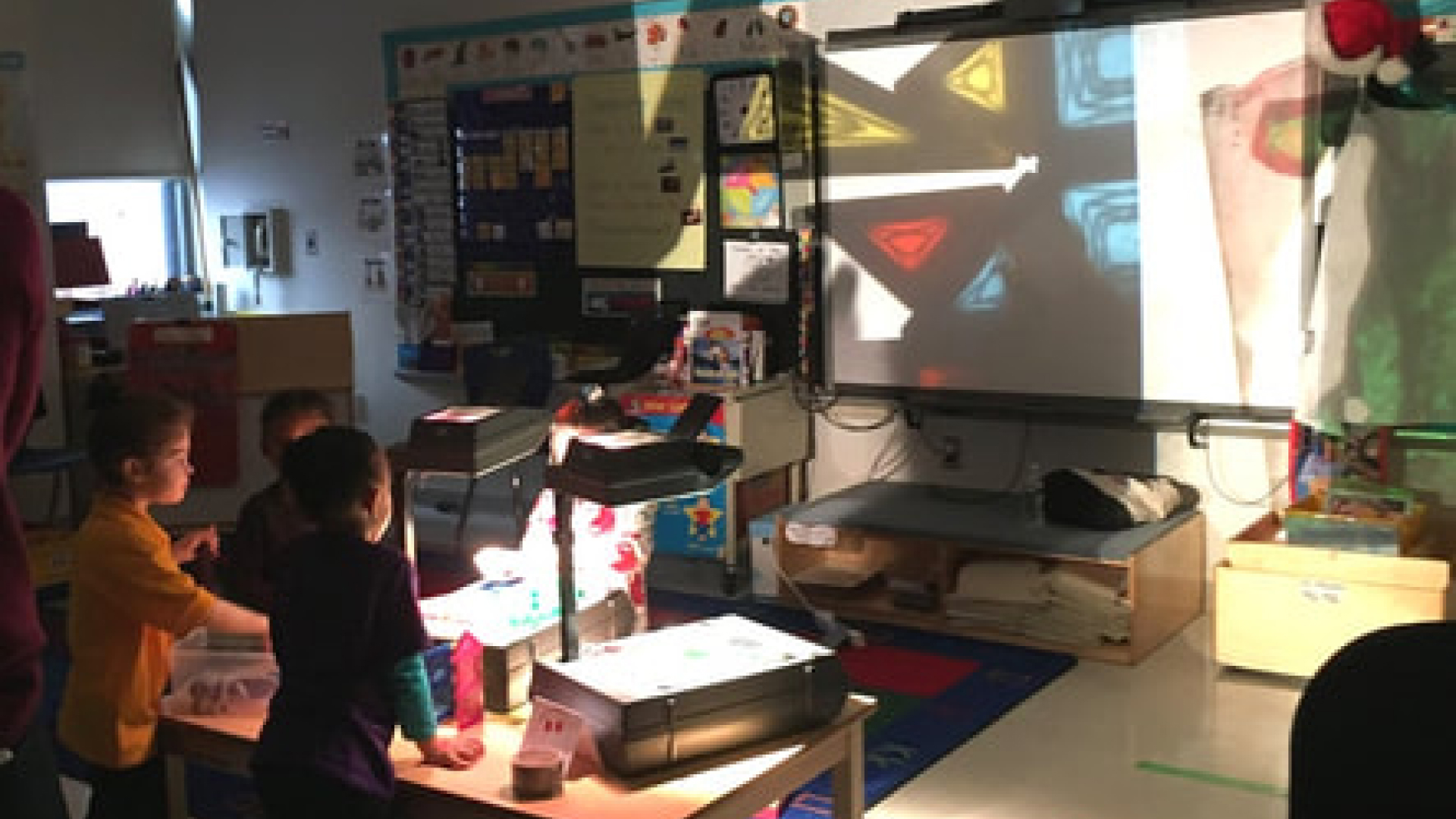

I contacted the Carnegie Mellon University Children’s School to sit in some of their playtimes. Observing their play settings informed the size of my object, and props and making kits informed the object and kit’s form language and capabilities.

I contacted the Carnegie Mellon University Children’s School to sit in some of their playtimes. Observing their play settings informed the size of my object, and props and making kits informed the object and kit’s form language and capabilities.

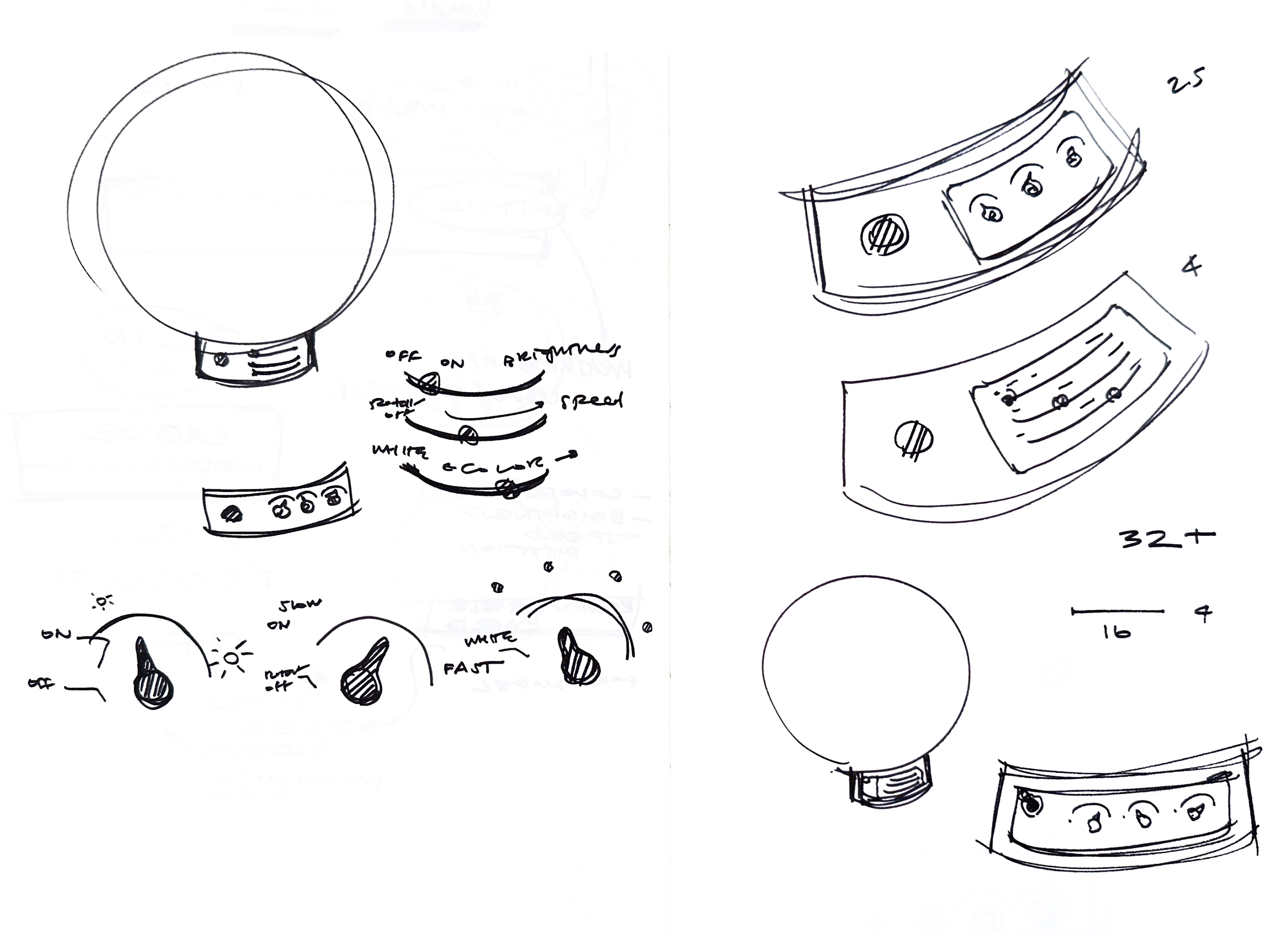

Form References

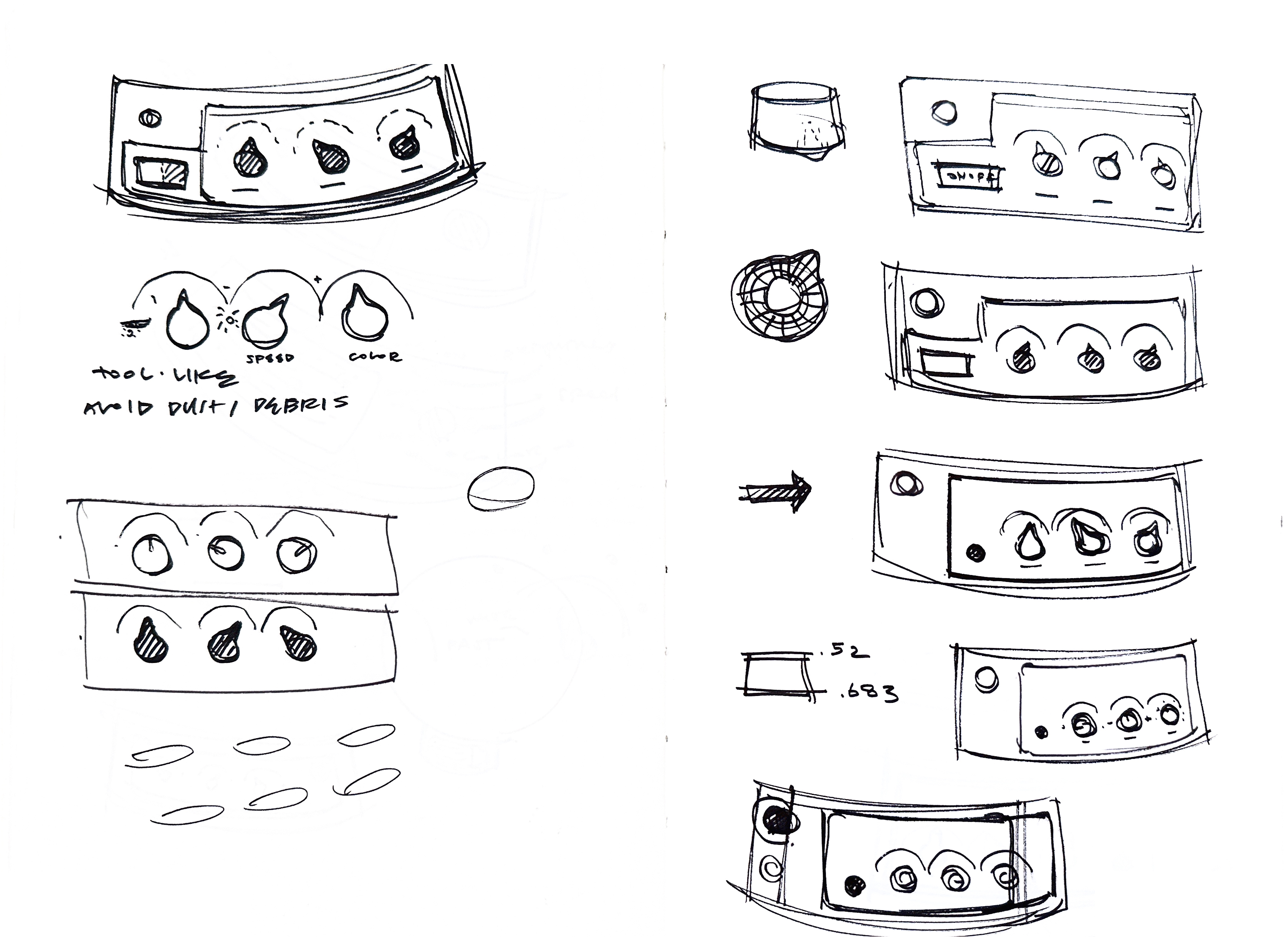

I wanted to avoid making the object look too “kiddie.” Instead, key words for the form language were tool-like and essential. Since the overall form factor is so distinct and circular, I wanted to embrace pure geometries and highlight 90 degree relationships, particularly using bent sheet metal.

I wanted to avoid making the object look too “kiddie.” Instead, key words for the form language were tool-like and essential. Since the overall form factor is so distinct and circular, I wanted to embrace pure geometries and highlight 90 degree relationships, particularly using bent sheet metal.

Internals

I borrowed an overhead projector to study its internals. Since my design would require more light than a regular overhead projector and therefore create more heat, I considered placement of the lights, fans, and mirrors.

I borrowed an overhead projector to study its internals. Since my design would require more light than a regular overhead projector and therefore create more heat, I considered placement of the lights, fans, and mirrors.

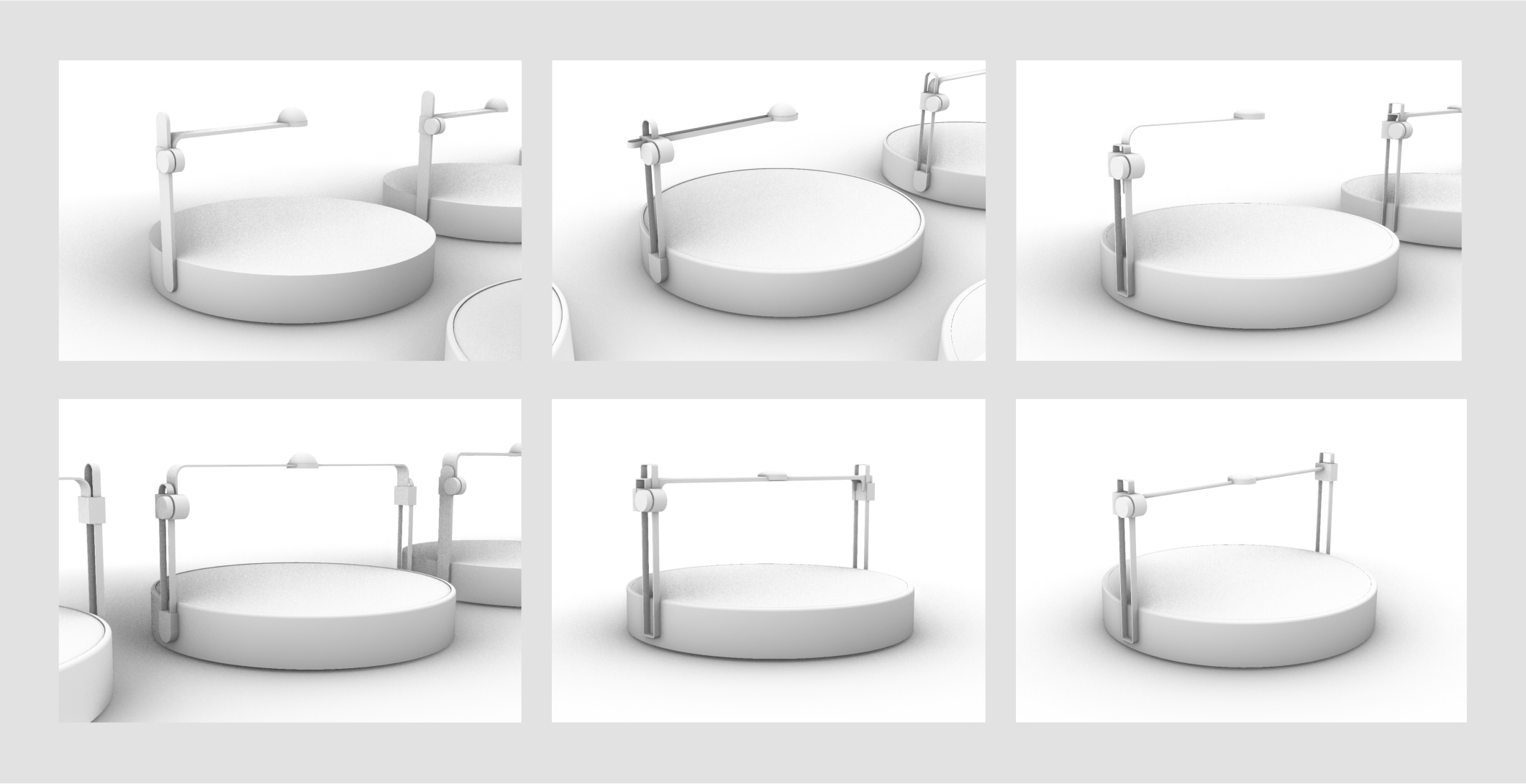

Form Development

Considerations included the number of poles, knob placement, direction of sheet metal bends, and cord, handles, and button integration.

Considerations included the number of poles, knob placement, direction of sheet metal bends, and cord, handles, and button integration.

Branding

Arc means part of a circle, analogous to the way each child using the object becomes part of a whole. It can also be used to describe the light formed by a connection between electrodes.

Arc means part of a circle, analogous to the way each child using the object becomes part of a whole. It can also be used to describe the light formed by a connection between electrodes.

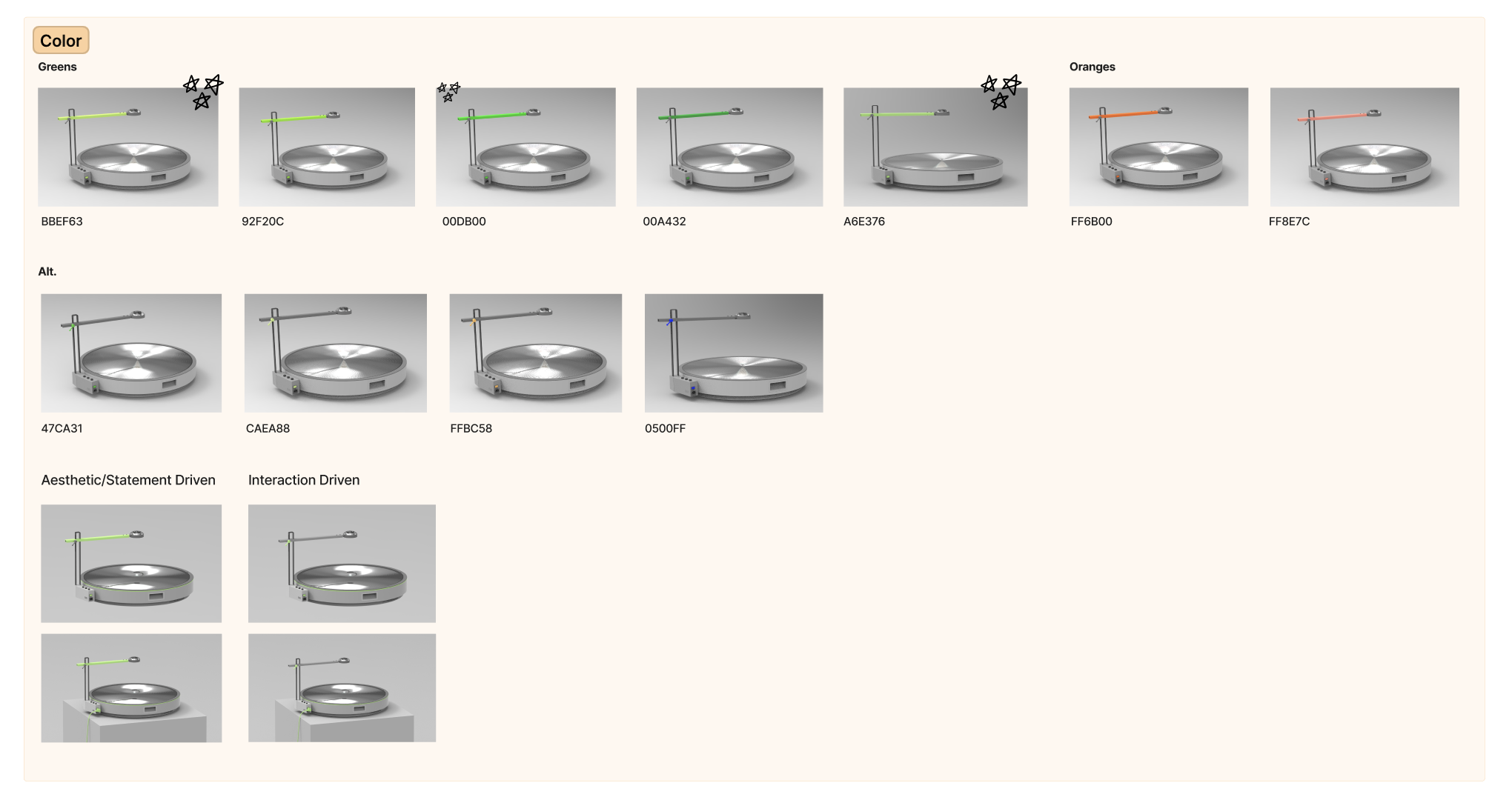

Color

Grey was chosen for the overall color so that the focus would be on the interaction, not so much the object itself. The light yellow-green acts as both a pop of color and guide for the interaction points.

Grey was chosen for the overall color so that the focus would be on the interaction, not so much the object itself. The light yellow-green acts as both a pop of color and guide for the interaction points.

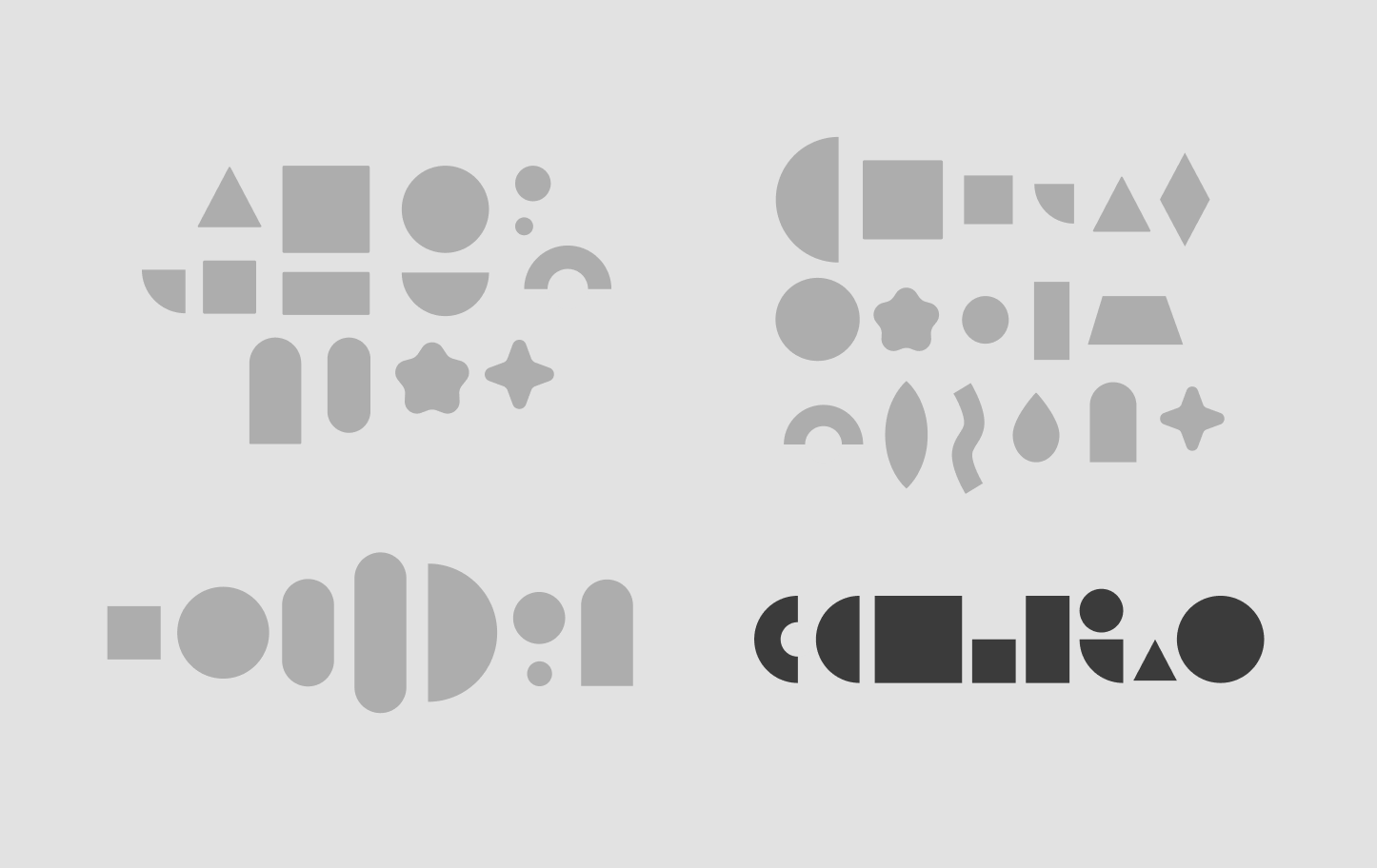

Tiles

Tile shapes and colors were kept primitive as to encourage the children to build freely from imagination.

Tile shapes and colors were kept primitive as to encourage the children to build freely from imagination.

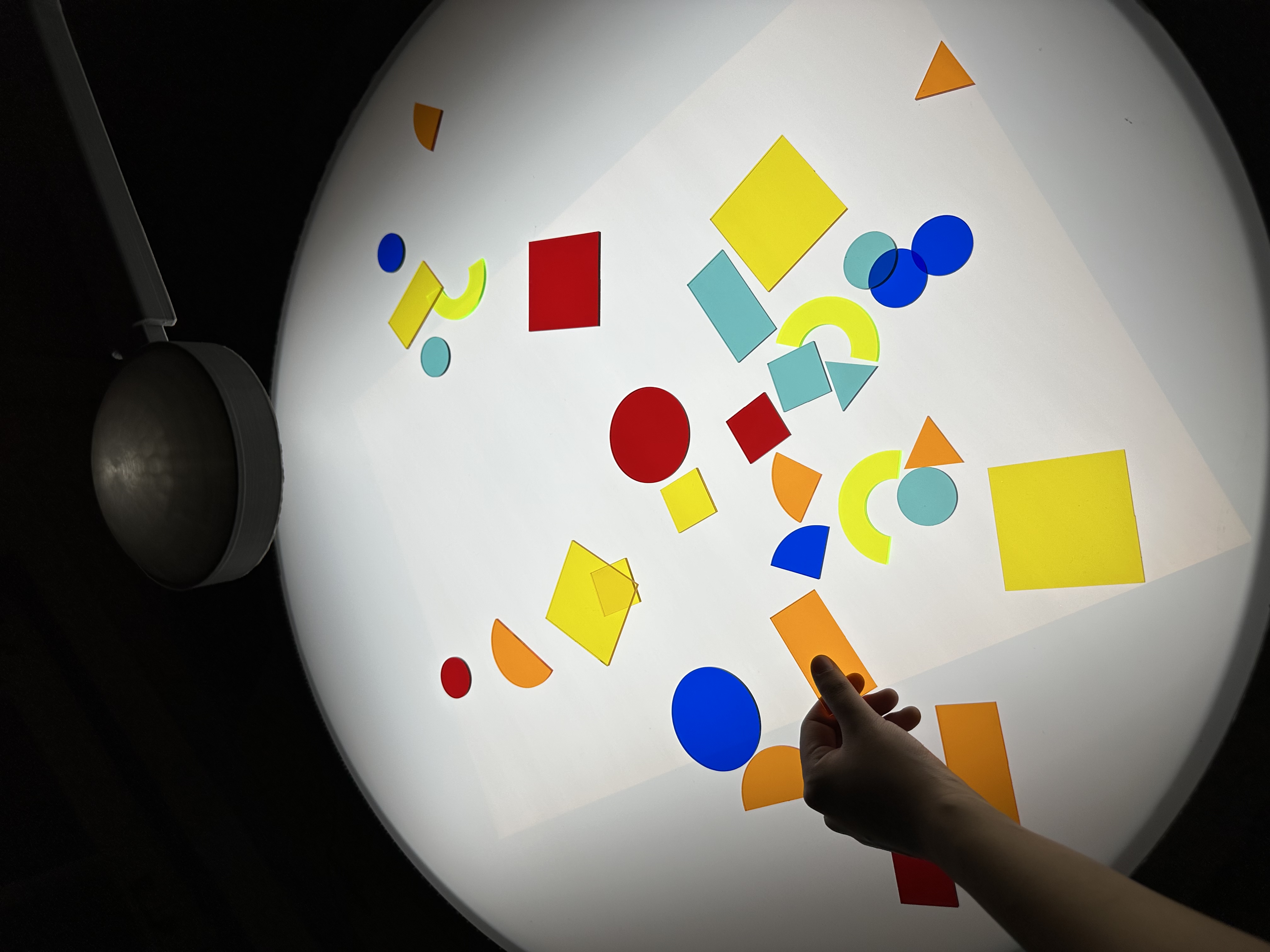

Form Model Building

The object’s size required a combination of cardboard modeling and 3D printing. A light table was placed inside to bring the interaction closer to concept.

The object’s size required a combination of cardboard modeling and 3D printing. A light table was placed inside to bring the interaction closer to concept.

Testing and Validation

I took the model back to the children’s school for a final round of validation.

I took the model back to the children’s school for a final round of validation.

Insights

It’s Intuitive, but Facilitation Helps

The surface and dry-erase markers were all they needed to see to get started. However, prompting of how we might build a neighborhood or forest, etc. around the circle helped define the interaction more clearly.

The surface and dry-erase markers were all they needed to see to get started. However, prompting of how we might build a neighborhood or forest, etc. around the circle helped define the interaction more clearly.

The Circular Surface Reads As a “World.”

They immediately understood the outer perimeter as the ground and the middle of the circle as the sky. They created rockets to blast off from the “ground” and meteors to fly around the “sky.”

They immediately understood the outer perimeter as the ground and the middle of the circle as the sky. They created rockets to blast off from the “ground” and meteors to fly around the “sky.”

They Make Up Their Own Rules

In one group, one boy created a maze of streets, while a girl created a house. When another boy started swirling a tornado around the image, the girl drew “magic hearts” around her house and the boy’s neighborhood to protect them from the tornado.

In one group, one boy created a maze of streets, while a girl created a house. When another boy started swirling a tornado around the image, the girl drew “magic hearts” around her house and the boy’s neighborhood to protect them from the tornado.

Everyone Participates

All the children— talkative or quiet, outgoing or shy— had a place around the table and actively contributed to the image.

All the children— talkative or quiet, outgoing or shy— had a place around the table and actively contributed to the image.

Feedback

“I love the fact that it’s a very simple, intuitive activity that all kids can participate in, just like playing in a sandbox or with a soccer ball. The light projection part definitely takes it a step further.” — Bailey, Teacher’s Assistant

“The kids love playing with light stuff. Whenever the university has an overhead projector they need to get rid of, they actually contact us! But they’re quite small, so the large circular surface is a game-changer for everyone to be able to sit around. This is something we’d love to have in the classroom.” — Mrs. S, Teacher

“I’m so glad you came to show us this!” — Clementine, Age 6

Show Day ︎ Special thanks to Jonathan Chapman, Josiah Stadelmeier, Steve Stadelmeier, and the CMU Children’s School.